Chemical & Engineering News

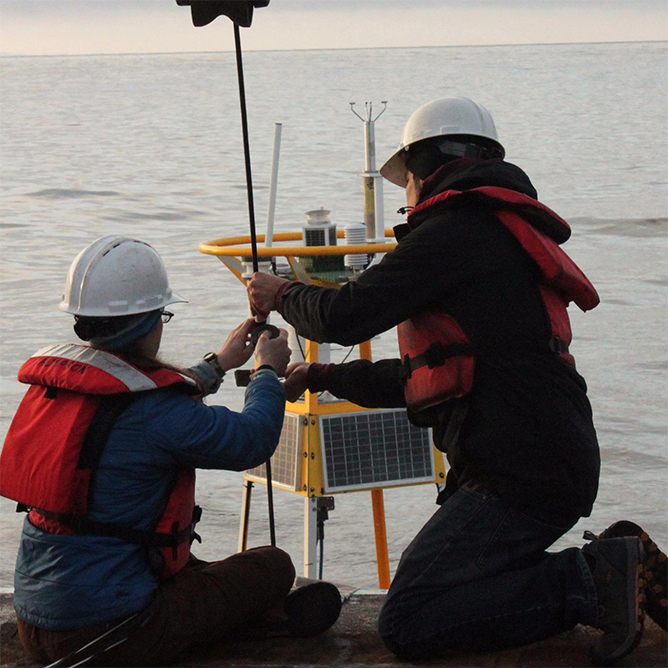

The path toCape Flattery is a twisty, moss-carpeted tunnel underneath red cedar and Douglas fir trees that crowd Washington state’s rugged coastline. Micah McCarty scrambles down the forest trail to a shoreline below, leaping across tide pools and slippery rocks to a point where waves break on shellfish beds. We’ve reached the northwesternmost point of the U.S. mainland, a craggy tip of the Olympic Peninsula that belongs to the Makah tribe.

This group of Native Americans has been fishing and harvesting here for the past 2,000 years. McCarty, the tribe’s 42-year-old former chairman, pulls out a pocket knife and squats down to scrape a handful of mussels and barnacles into his hand. “We call them slippers and boots,” he says. “I’ll make them into a Makah paella tonight.”

McCarty and his family grew up picking these marine delights along the coast. Oysters, clams, cockles, barnacles, and other types of mollusks and shellfish have always been part of the Makah diet, as well as the tribe’s culture. The shells are used both as beads in ceremonial regalia and as musical instruments. But now, changes in the global climate have led to rising ocean acidification that has put in peril the future of the Makah harvest.