ClimateWire

Most of the research on ocean acidification has focused on the West Coast, where scientists have known upwelling from the deep ocean makes those coastal environments particularly vulnerable to acidification spurred by climate change.

Work by researcher Zhaohui “Aleck” Wang, a chemical oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and a team of colleagues who surveyed the entire Atlantic coast shows that the Gulf of Maine in the northeast Atlantic may also be at risk.

“[This] study provides the first systematic survey of the seawater inorganic carbon chemistry in coastal waters stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of Maine,” said Scott Doney, a senior scientist and director of Woods Hole’s Ocean and Climate Change Institute.

“Particularly interesting was the finding of relatively acidic waters along the bottom of the Gulf of Maine,” Doney added.

Wang also highlighted this finding. “Traditionally, the Northeast [ocean] water is viewed as a lower-risk area, and now we are realizing that may not be the case,” Wang said. “This paper basically says, wait a minute.”

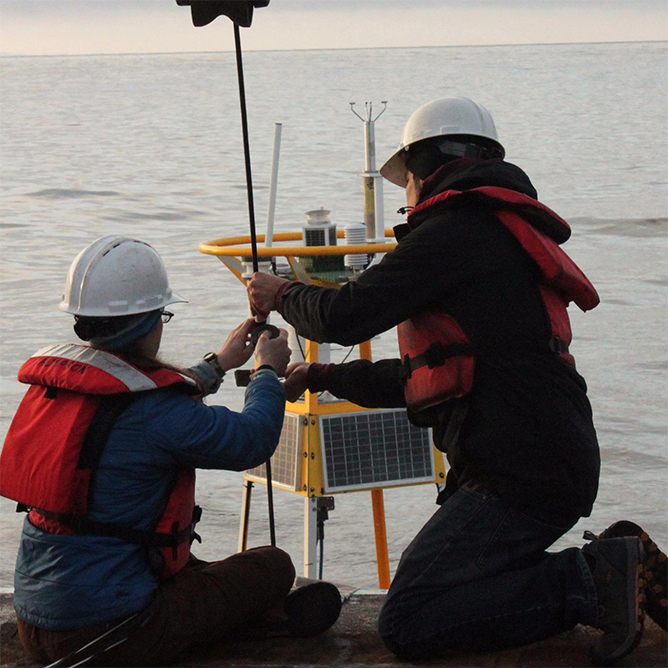

In the summer of 2007, Wang and his colleagues took a research vessel all the way up the east coast, sampling ocean water from the Gulf of Mexico northward. They were trying to determine the amount of carbon dioxide and other forms of carbon dissolved in the ocean. They were also trying to learn how sensitive each part of the coast was to acidification.

Risk to shellfish

The results, published in January in the journal Limnology and Oceanography, show that the Gulf of Maine is likely to be vulnerable to acidification, Wang said.

Oceans absorb carbon dioxide, and the reactions that take place after the carbon dioxide is dissolved lower the pH of the water, making it more acidic. Acidification has already caused problems in the Pacific Northwest, where it has hurt the ability of shellfish like oysters to make their calcium carbonate shells.

However, little was known about the acidity of the ocean along the east coast. That’s why Wang’s study is important, said Richard Feely, a senior scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

Feely performed pioneering research on ocean acidification in the Pacific Northwest and has even helped West Coast oyster producers come up with solutions to the problems acidification was causing them — although, he cautioned, increasing acidification caused by climate change will necessitate different additional adaptation solutions.

“By 2050, as much as 50 percent of waters will be corrosive,” or very acidified, Feely said.

Carbon dioxide enters coastal waters from the atmosphere, but acidification can also be triggered by nutrient-rich rivers that run into the ocean. Those rivers pick up nutrients like excess fertilizer from farms and from other sources, causing algal blooms that eventually lead to elevated levels of CO2 in the oceans the rivers flow into.

More research to be done

Yet although the Gulf of Mexico receives a lot of nutrient-rich runoff from the Mississippi River, it is less vulnerable to acidification because it has a higher buffering capacity than the Gulf of Maine, Wang said, meaning it can absorb more carbon dioxide without a change in pH.

“If you put the same amount of CO2 into both the Gulf of Maine and the Gulf of Mexico right now, the ecosystem in the Gulf of Maine would probably feel the effects more dramatically,” he added.

In the future, Wang said, he will be working with a team of researchers to look at how the low pH and increasing acidity in the Gulf of Maine might affect shellfish including tiny zooplankton, which are a food source for other species in the ocean. He’d also like his team to look at impacts to lobsters one day, since they are of key economic importance in the region.

“The problem will likely grow with time, with the burning of more fossil fuels and the buildup of excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,” said Woods Hole’s Doney.

Wang also believes warming might add to the Gulf of Maine’s acidity problems by melting sea ice and glaciers that feed the Labrador Sea. Fresh water from those sources is more acidic than ocean water, and the Labrador Coastal Current brings that fresh water down into the Gulf of Maine.

Data already show that the Gulf of Maine is becoming less saline, likely because of more fresh water flowing in. He suspects this will also lead to additional acidification.

“But how much lower and how much it will continue into the future is a big question mark,” Wang said.

Want to read more stories like this?

Click here to start a free trial to E&E — the best way to track policy and markets.