Our Changing Ocean

What is Ocean Acidification?

Our ocean’s chemistry is changing, causing impacts to marine life and livelihoods.

Our Changing Ocean

Our ocean’s chemistry is changing, causing impacts to marine life and livelihoods.

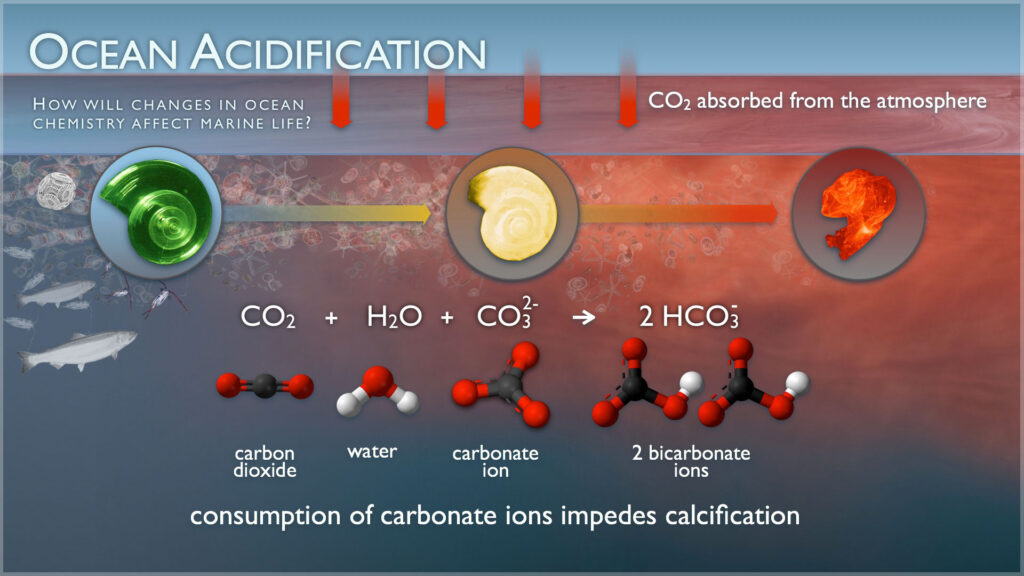

Ocean acidification occurs when the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide. This causes a fundamental and global change in the chemistry of the ocean.

Increases in carbon dioxide (known as CO2) in the atmosphere drive corresponding increases in dissolved CO2 within the surface waters of our ocean. This dissolved CO2 reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid (H2CO3). Carbonic acid breaks apart to form bicarbonate ions (HCO3–) and hydrogen ions (H+). Hydrogen ions (H+) act like free agents that cause the seawater to become more acidic. We measure this using pH (H represents hydrogen ions). The free agent hydrogen ions also react with carbonate ions (CO32-) to form bicarbonate (HCO3–), making carbonate ions relatively less abundant. Next, find out why this matters next.

There are four ocean chemistry parameters we measure to understand ocean chemistry related to acidification. Researchers need to measure two of these parameters to be able to calculate the others and characterize conditions.

Learn about what we measure, and why. Download the infographic for even more.

When the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide, chemical reactions create hydrogen ions that act like free agents, able to react with other compounds. Two ways we track ocean acidification are through pH and total alkalinity (TA). pH is a measure of how many free hydrogen ions are in the seawater. The more carbon dioxide in the ocean, the more these free agents are created, causing lower pH (more acidic).

The partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) tells us how much carbon dioxide is in seawater. This information helps us understand ocean carbonate chemistry and biological productivity in the region. pCO2 increases when the ocean absorbs more CO2 from the atmosphere with elevated emissions.

Alkalinity is the ocean’s buffering system against increasing acidity. Total alkalinity is a measure of the concentration of buffering molecules like carbonate and bicarbonate in the seawater that can neutralize acid.

Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) tells us how much non-biological carbon is in seawater. Inorganic carbon comes in three main forms that we measure for DIC: carbon dioxide ( CO2), bicarbonate (HCO3-), and carbonate (CO32-). Understanding DIC can help us determine the balance of carbonate forms in the ocean and the likelihood of ocean acidification.

Local coastal processes can cause acidification.

Coastal acidification includes local changes in water chemistry that can arise from human inputs on land as well as natural processes.

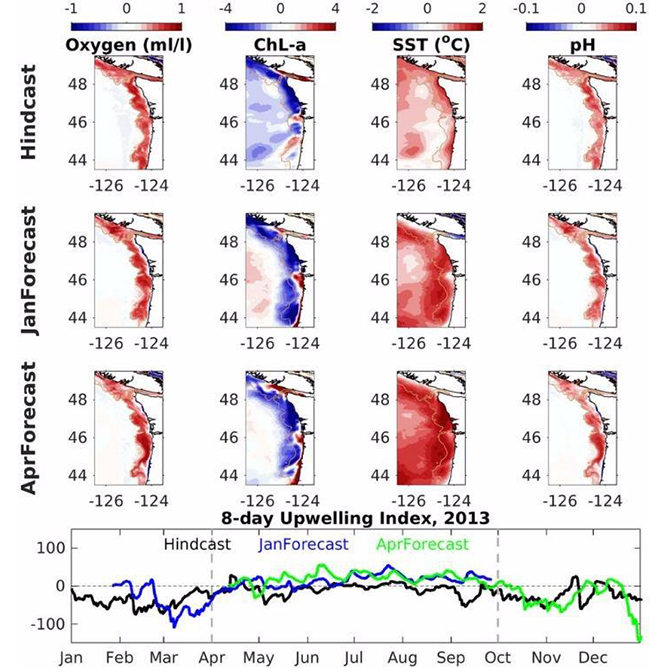

Coastal upwelling is a natural process that brings deeper,

more acidic waters to the surface ocean in the coastal zone. Upwelling occurs primarily

on the western boundaries of continents, but the timing, duration and severity of upwelling events may increase with climate change.

Human impacts include excess nutrient run-off (e.g. nitrogen and organic carbon) from land. This runoff can cause increases in algal growth, commonly known as ‘blooms’. When these algal blooms die, they consume oxygen and release carbon dioxide and increasing acidity.

Coastal acidification can also occur with changes in water column circulation occur. Changes in wind, temperature, or salinity changes can have both natural and human causes.

The impacts of ocean acidification depend on the timing, duration, and severity of acidification, how marine life and ecosystems respond, and the effects on people who depend on healthy coastal ecosystems.

Freshwater bodies like the Great Lakes also experience acidification. Researchers project that pH, the measure of how acidic or alkaline the water body is, will decline at a rate similar to that of the oceans in response to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere isn’t the only source of acidification. The Great Lakes are also recovering from acid deposition. The Midwestern and Northeastern United States experienced an increase in deposition of sulfuric and nitric acids from the early 20th century until air-quality regulations mitigated this trend.

Present-day mean pH and alkalinity vary according to the geology of each lake basin, with Superior having the most acidified waters and Michigan the least acidified. In addition, considerable short-term spatial and temporal variability in pH occurs, driven largely by varying rates of photosynthesis, respiration, and seasonal mixing. There has not been any long-term robust monitoring of acidification in the Great Lakes system until recently.

What’s at stake from ocean acidification may be different depending on where you live. As a community member, you can take a larger role in educating the public about ocean acidification.

The NOAA Ocean Acidification Program aims to provide information to help people adapt to the consequences of ocean acidification. Check out our near real-time data and support tools that include:

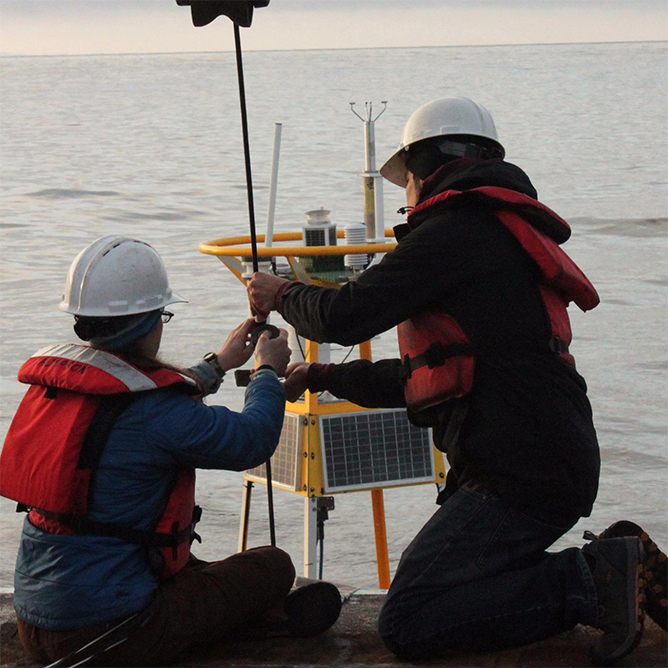

NOAA works to better understand how to mitigate and adapt to acidification on local, regional and national scales. Continued research that uses innovative technologies and approaches provides better information faster.

The OAP works closely with coastal state governments, on-the-ground networks, impacted industries, and NGOs to develop their responses to ocean acidification. See how we take action by supporting legislation development and reporting for ocean acidification research.

Bioeconomic models are a multidisciplinary tool that use oceanography, fisheries science and social science to assess socioeconomic impacts. Funded by the Ocean Acidification Program, researchers at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center use a bioeconomic model to study the impacts of ocean acidification on Eastern Bering Sea crab, northern rock sole and Alaska cod. The goal is to predict how ocean acidification will affect abundance yields and income generated by the fisheries. This work informs the potential economic impacts of ocean acidification and future decision making and research planning.

Long-term declines of red king crab in Bristol Bay, Alaska may be partially attributed to ocean acidification conditions. These impacts may be partially responsible for the fishery closures during the 2021–2022 and 2022–2023 seasons. Researchers found that ocean acidification negatively impacts Alaskan crabs generally by changing physiological processes, decreasing growth, increasing death rates and reducing shell thickness. Funded by the Ocean Acidification Program, scientists at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continue to investigate the responses of early life history stages and study the potential of various Alaska crabs to acclimate to changing conditions. Results will inform models that will use the parameters studied to predict the effects of future ocean acidification on the populations of red king crab in Bristol Bay as well as on the fisheries that depend on them. Fishery managers will better be able to anticipate and manage stocks if changing ocean chemistry affects stock productivity and thus the maximum sustainable yield.

Understanding seasonal changes in ocean acidification in Alaskan waters and the potential impacts to the multi-billion-dollar fishery sector is a main priority. Through work funded by NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program, the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory developed a model capable of depicting past ocean chemistry conditions for the Bering Sea and is now testing the ability of this model to forecast future conditions. This model is being used to develop an ocean acidification indicator provided to fisheries managers in the annual NOAA Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem Status Report.

The NOAA Ocean Acidification Program (OAP) works to prepare society to adapt to the consequences of ocean acidification and conserve marine ecosystems as acidification occurs. Learn more about the human connections and adaptation strategies from these efforts.

Adaptation approaches fostered by the OAP include:

Using models and research to understand the sensitivity of organisms and ecosystems to ocean acidification to make predictions about the future, allowing communities and industries to prepare

Using these models and predictions as tools to facilitate management strategies that will protect marine resources and communities from future changes

Developing innovative tools to help monitor ocean acidification and mitigate changing ocean chemistry locally

Drive fuel-efficient vehicles or choose public transportation. Choose your bike or walk! Don't sit idle for more than 30 seconds. Keep your tires properly inflated.

Eat local- this helps cut down on production and transport! Reduce your meat and dairy. Compost to avoid food waste ending up in the landfill

Make energy-efficient choices for your appliances and lighting. Heat and cool efficiently! Change your air filters and program your thermostat, seal and insulate your home, and support clean energy sources

Reduce your use of fertilizers, Improve sewage treatment and run off, and Protect and restore coastal habitats

You've taken the first step to learn more about ocean acidification - why not spread this knowledge to your community?

Every community has their unique culture, economy and ecology and what’s at stake from ocean acidification may be different depending on where you live. As a community member, you can take a larger role in educating the public about ocean acidification. Creating awareness is the first step to taking action. As communities gain traction, neighboring regions that share marine resources can build larger coalitions to address ocean acidification. Here are some ideas to get started: