NOAA Research, Laura Newcomb

</ br>

For Bill Mook, coastal acidification is one thing his oyster hatchery cannot afford to ignore.

Mook Sea Farm depends on seawater from the Gulf of Maine pumped into a Quonset hut-style building where tiny oysters are grown in tanks. Mook sells these tiny oysters to other oyster farmers or transfers them to his oyster farm on the Damariscotta River where they grow large enough to sell to restaurants and markets on the East Coast.

The global ocean has soaked up one third of human-caused carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions since the start of the Industrial Era, increasing the CO2 and acidity of seawater. Increased seawater acidity reduces available carbonate, the building blocks used by shellfish to grow their shells. Rain washing fertilizer and other nutrients into nearshore waters can also increase ocean acidity.

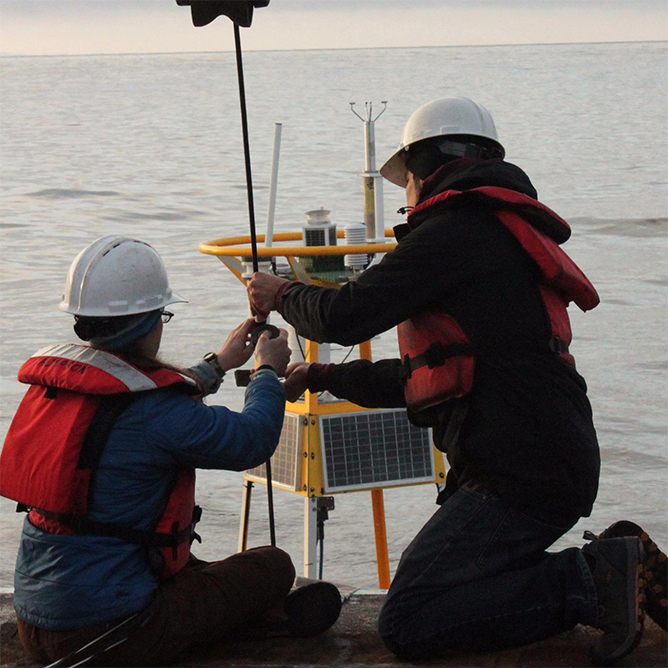

Back in 2013, Mook teamed up with fisherman-turned-oceanographer Joe Salisbury of the University of New Hampshire to understand how changing seawater chemistry may hamper the growth and survival of oysters in his hatchery and oyster farm.

Salisbury and his team adapted and installed in the hatchery sophisticated technology that Mook calls “the black box.” Sensors housed inside a heavy black plastic case the size of a breadbox estimate the amount of carbonate in seawater pumped into the hatchery by measuring carbon dioxide and the alkalinity, or the capacity of the water to buffer against increases in acidity. The “black box” was developed with funding from the NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program and Integrated Ocean Observing System.

Mook compares ocean acidification to a train barreling down the tracks headed for his business. By measuring the year-to-year changes in carbonate and matching that against how well his oysters do in a particular year, he says he’ll understand how oysters grow under different conditions. These tools help him learn how fast and at what time the train may arrive.

“We see a growth opportunity for this equipment,” Salisbury says. He and his team are now using “black boxes” in the waters off Puerto Rico to map where changes in acidity may contribute to coral reef erosion. Starting this year, NOAA Ship Henry B. Bigelow will be outfitted with black boxes to collect carbonate chemistry data during fisheries surveys along the eastern seaboard. NOAA will use this data to help improve predictions of how ocean acidification may affect valuable resources and the people, like Mook, whose livelihoods depend on them.

Editor's note: Laura Newcomb is a Sea Grant Knauss Fellow at NOAA Research's Office of Laboratories and Cooperative Institutes.

For more information, please contact Monica Allen, director of public affairs at NOAA Research, at 301-734-1123 or monica.allen@noaa.gov