Building resilience to ocean acidification from sea to shell

Mook Sea Farm, located on the Damariscotta River in midcoast Maine, produces over 120 million juvenile oysters each year. The farm’s water comes directly from the river and changes in environmental conditions affect hatchery production. During the 2008-2009 season, Mook experienced decreased larval production due to high levels of precipitation decreasing the carbon dioxide (CO2) buffering capacity in hatchery water. This short-term acidification event negatively impacted production of larval oysters.

Background Image: Floating oyster cages at Mook Sea Farm

To address short-term acidification, specialists at Mook began buffering larval water tanks after large rain storms. The extra buffering capacity allows larvae to thrive, reducing the impact of short-term acidification events. Now, the group monitors water chemistry in their reservoir tanks and adds buffer as needed. In static systems, this process is done by hand. In flow-through systems, a controller adds buffer when the tank’s pH drops below 8.1. This small-scale monitoring system allows the oyster hatchery to stay in business despite acidification events.

Background Image: Oysters in hand

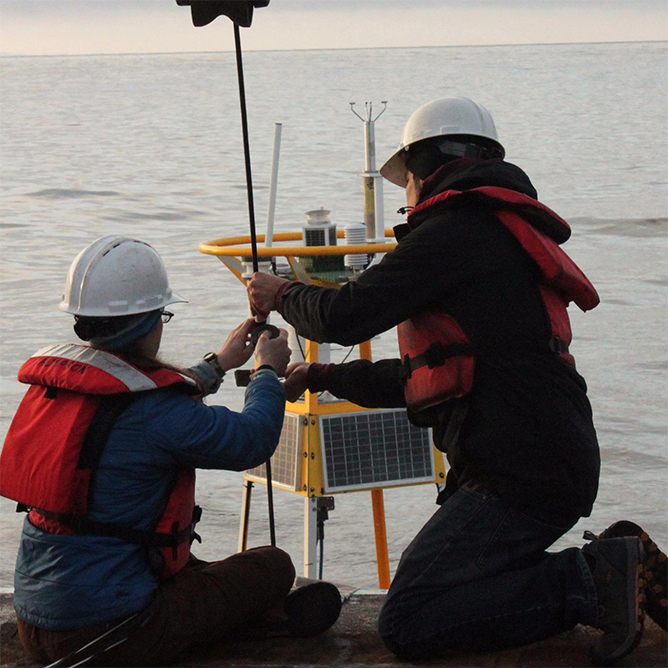

Ocean monitoring at a variety of scales helps mitigate the negative impacts of ocean acidification to businesses like Mook Sea Farm by helping us know where and when ocean acidification occurs.

The third East Coast Ocean Acidification cruise (ECOA-3) exemplifies large scale, coastal carbon system monitoring that produces high quality data for the coast. This 40-day cruise travels from Nova Scotian waters to the southernmost points of the east coast near Florida. Along the cruise, scientists will measure carbon parameters, biological activity, and physical ocean properties to better understand the state of acidification along the United States east coast.

Background Image: Water sample collection from a CTD

ECOA-3 began its journey sampling in the Gulf of Maine, an area known for its diverse and productive fisheries that are important culturally and economically for its residents and the nation. Though the ECOA-3 cruise and Mook’s hatchery-specific monitoring operations operate on different scales, the systems are interconnected.

Meredith White, Director of Research and Development at Mook Sea Farm, emphasizes that “we’re operating in an ecosystem that is all connected, so changes happening in the open ocean will eventually link to us.”

She goes on to note that:

Understanding what changes are happening and at what rates is going to help us build resiliency into our industry. Data that ECOA-3 collects are critical to that goal, even if they are not measurements taken right off our dock.

Meredith White, Mook Sea Farm

Background Image: A worker at Mook Sea Farm sorts through oyster seeds

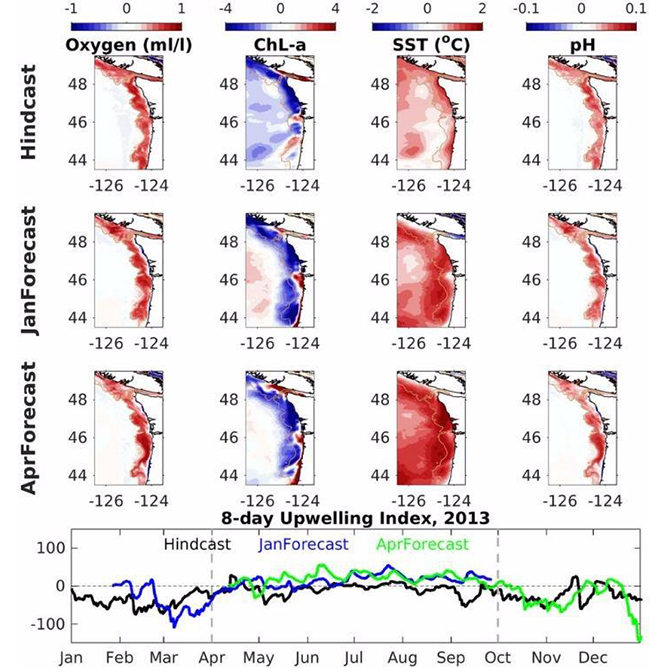

Absorption of carbon dioxide emissions, coastal inputs, and large ocean currents make the Gulf of Maine susceptible to acidification. Findings by east coast researchers Joe Salisbury, Samantha Siedleicki and colleagues indicated that while regional warming of the Gulf could slow down acidification caused by human emissions, acidification will likely overcome these compensating effects by 2050. Marine life in the productive region may be exposed to conditions that might cause energetic strain – making it harder to make a living for them and the people who depend on them. To track ocean and coastal acidification, we need to maintain local, regional, and global monitoring networks.

Continued monitoring efforts at all scales ensure that we are best prepared for our changing ocean and the effects that ripple up through our socioeconomic system.

NOAA Ocean Acidification Program, 2022

Background Image: Shucked oyster