Mission

The Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification (IWG-OA) aims to coordinate ocean acidification research, monitoring and engagement across the federal government to better assess the impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and coastal communities and support the development of mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Act of 2009 (FOARAM Act; 33 U.S.C. Chapter 50, Sec. 3701-3708) directed the Subcommittee on Ocean Science and Technology (SOST) to create an Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification (IWG-OA). The IWG-OA was chartered by SOST in October 2009 and includes representatives from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Science Foundation (NSF), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of State (DOS), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Parks Service (NPS), Smithsonian Institution (SI), the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NOAA chairs the group. The agencies represented on the IWG-OA have mandates for research and/or management of resources and ecosystems likely to be impacted by ocean acidification. The group meets regularly to coordinate ocean acidification activities across the Federal government to fulfill the goals of the FOARAM Act.

Latest News

The Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification is hosting the second webinar in the Acidification & Estuaries Webinar Series on October 23, 2024 at 2:00pm ET. This webinar will give an overview of the state of the science related to acidification in estuaries and discuss remaining research gaps. Speakers will

The following federal agencies participate in the IWGOA and are actively working to develop ocean acidification adaptation and mitigation strategies. The IWG-OA has regular meetings to share information on activities related to the seven thematic areas of the Strategic Research Plan:

- Research to understand responses to ocean acidification

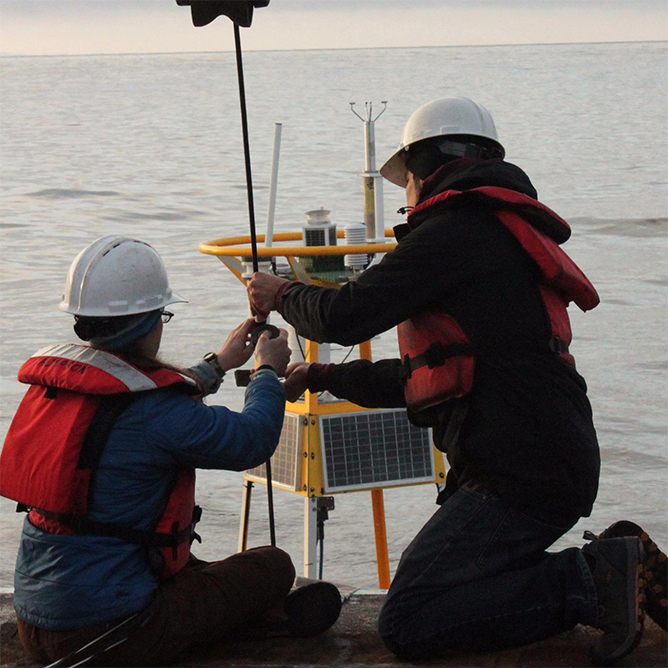

- Monitoring of ocean chemistry and biological impacts

- Modeling to predict changes in the ocean carbon cycle and impacts on marine ecosystems and organisms

- Technology development and standardization of measurements

- Assessment of socioeconomic impacts and development of strategies to conserve marine organisms and ecosystems

- Education, outreach, and engagement strategy on ocean acidification

- Data management and integration

Click on a logo below to learn more about each agency’s role in with the IWG-OA

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in the Department of the Interior is responsible for managing the use of oil, gas, renewable, and marine mineral resources along the outer continental shelf of the United States. BOEM is contributing to the knowledge of ocean acidification through research activities taking place along the West Coast and in Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico. BOEM’s Environmental Studies Program develops, conducts and oversees world-class scientific research specifically to inform policy decisions regarding development of outer continental shelf energy and mineral resources. This research includes the topic of ocean acidification as it applies to BOEM’s jurisdictional purview. In particular, an increased understanding of ocean acidification-induced biogeochemical changes informs BOEM’s cumulative impacts analysis as part of National Environmental Policy Act, which considers environmental impacts from energy development in addition to other potential stressors, such as climate change. Further information is needed to assist BOEM in predicting and detecting the effects of offshore energy activities by describing baseline environmental conditions and if and how they are shifting. BOEM is working to address these information needs and will also use information collected by other entities, including Federal agencies.

Environmental Protection Agency

The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) mission is to protect human health and the environment, which includes identifying impacts on the Nation’s coastal waters due to ocean acidification. EPA authorities under the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act can play an important role in addressing ocean acidification. EPA’s activities under the Clean Air Act to mitigate greenhouse gases have implications for ocean acidification because atmospheric concentrations of CO2 from anthropogenic sources are considered to be the primary driver of acidification in the open ocean and in the waters that ocean circulation brings to coastal environments. EPA and state programs under the Clean Water Act come into play in two ways: 1) acidification may affect the ability of coastal waters to support states’ applicable water quality standards; and 2) these programs help states identify and address land-based sources of pollution (e.g., nutrients) that are considered by the scientific community to be an important driver of coastal acidification.

EPA has recently developed a nationally-oriented ocean and coastal acidification program that includes applied research on ecological responses to acidification, efforts to enhance monitoring in coastal waters, and modeling to assess local drivers and forecast environmental and socioeconomic consequences of acidification. EPA’s Office of Research and Development (ORD) provides scientific support on ocean and coastal acidification to the agency’s air and water programs and regions. Prior to FY 2016, ORD ocean acidification research was primarily incidental, capitalizing on sampling opportunities that were driven by other programmatic priorities. Beginning in FY 2016, ORD is conducting targeted research on the causes and responses to acidification and hypoxia in the coastal environment, with a strong emphasis on the role of nutrients. This includes field experiments and sampling activities, laboratory investigations of the response of aquatic life to acidification in EPA’s marine laboratories, and water quality modeling studies that include carbonate chemistry.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) responds to the FOARAM through its role as vice-chair of the IWG-OA and by funding research that contributes to increased understanding of ocean acidification. NASA has supported targeted, approximately annual research opportunities to facilitate ocean acidification research since 2007, details of which are included in the IWG-OA’s biennial reports to Congress. Funded research utilizes NASA's satellite remote sensing observations, as well as in situ observations and models, to support the FOARAM Act's objectives and NASA's mission. NASA's ocean acidification research may also facilitate operational and management responsibilities of other agencies included in the FOARAM Act, such as the requirement to develop adaptation strategies to conserve aquatic ecosystems vulnerable to the effects of ocean acidification.

To study the Earth as a whole system and understand how it is changing, NASA develops and supports a large number of Earth observing missions. These missions provide Earth science researchers with the necessary data to address key questions about global climate change. They provide global observations and data about the Earth, and are used to estimate properties of the Earth system. These data include information on the land, ocean, atmosphere, solid Earth, and cryosphere.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

While the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) does not have a large program specifically focused on ocean acidification, NIST provides a number of measurement and calibration capabilities that support the efforts of other agencies (e.g., NASA, NOAA) and the broader research community to monitor ocean changes, including acidification. For example, NIST provides a number of advanced satellite calibration standards, including color standards and sensor calibrations to support the Marine Optical Buoy program. Additionally, NIST, through the Hollings Marine Laboratory in Charleston, South Carolina, runs the Marine Environmental Specimen Bank, which cryogenically banks well-documented environmental specimens collected as part of other agency marine research and monitoring programs. In 2010, NIST expanded this effort through the establishment of the NIST U.S. Pacific Islands Program to help address environmental and ecological questions that are unique to the region. This program includes collaboration with NOAA; other Federal, state, local, and regional agencies; private organization; universities; and research institutes to establish a biorepository in the region and to advance measurement capabilities for environmental health research. A major element of this effort relevant to ocean acidification is a new coral reef banking program known as the Archive of Coral Ecosystem Specimens. The new coral reef banking program will create a formal repository of calcium carbonate skeletons and tissues from corals and other reef taxa to serve as a resource for long-term monitoring and research. Localized stressors, such as impaired water quality, and global climate stressors, such as thermal stress and ocean acidification, impact elemental/isotopic signatures and biomarkers in carbonate skeletons and tissues that will be measured and archived to record past, present, and future environmental conditions and the associated organismal responses.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Understanding ocean acidification and developing reliable projections for how ocean acidification will affect living marine resources drives NOAA’s work on ocean acidification. NOAA’s activities on these topics are necessary for sustainably managing living marine resources in a changing world, enabling local communities to better understand, prepare for, and adapt to changes, and informing national and international carbon assessments and mitigation discussions. NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program (OAP) was established under Section 12406 of the FOARAM Act to oversee and coordinate ocean acidification research, monitoring, and other activities consistent with the Strategic Research Plan. As part of its responsibilities, the OAP incorporates a competitive, merit-based process for awarding grants on ocean acidification research. To date, the OAP has provided grants for research projects that explore the effects of ocean acidification on ecosystems and human socioeconomics.

National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) in the Department of the Interior manages all United States national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties. The National Park Service Organic Act of 1916 provides the NPS with a clear mission statement: “To conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wild life therein to provide for the enjoyment of the same in a manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” The NPS is entrusted with conserving 79 ocean parks, including over 10,000 shoreline miles and over 2 million water acres, including many tidally influenced estuaries. Marine parks are distributed around the United States from tropical to polar environments, including Alaska, the Pacific coast, the South Pacific islands, the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic coast, and the Caribbean. These parks house a wide variety of marine life and span a diverse array of habitats including coral reefs, kelp forests, seagrass beds, rocky and sandy shorelines, and glaciated fjords. Ocean acidification will likely influence all United States marine parks. Understanding the effects of ocean acidification is necessary to inform actions to conserve natural resources within these parks. Maintaining resilient marine ecosystems through restoration and species protection are positive actions the NPS can take to combat the effects of ocean acidification. The NPS represents a unique spatial network of marine habitats and natural resources that are ideal for ocean acidification research, monitoring, and public outreach. Such activities are central to the mission of the National Park Service to conserve these special areas.

National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent Federal agency responsible for advancing science, engineering, and science and engineering education in the United States. The agency is the funding source for approximately 24 percent of all federally supported fundamental research conducted by United States colleges and universities. Through a competitive, transparent, and in-depth merit review process, NSF seeks and supports the best ideas, tools, facilities, and people to expand the frontiers of knowledge.

NSF OCEAN ACIDIFICATION PROJECT SUPPORT

NSF supports basic research concerning the nature, extent, and impact of ocean acidification on oceanic environments in the past, present, and future. NSF is committed to research that seeks to understand; 1) the chemistry and physical chemistry of ocean acidification; 2) how ocean acidification interacts with processes at the organismal level; and 3) how the Earth system history informs understanding of the effects of ocean acidification on the ocean now and in the future.

Beginning in FY 2010, NSF initiated targeted solicitations for ocean acidification research as part of the NSF-wide Climate Research Investments and Science, Engineering and Education for Sustainability activities. During the five years these targeted solicitations were active, NSF invested over $50M in support of basic research on ocean acidification. No other targeted ocean acidification solicitations are expected under these NSF-wide activities.

United States Department of Agriculture

USDA, in its partnerships with other Federal agencies as a member of the National Ocean Council, supports continuing efforts that address recommendations made by the National Policy for the Stewardship of the Ocean, Our Coasts, and the Great Lakes Task Force. By promoting and implementing sustainable agricultural programs and practices on land and sustainable aquaculture practices in freshwater and saltwater environments, USDA programs will improve the health of the ocean, coasts, and Great Lakes as well as provide jobs important in the revitalization of our rural and coastal communities.

Water connects farms across the United States to coastal communities and the ocean. USDA conducts and funds research, technology transfer, and extension education programs that address issues related to climate change, nutrient runoff, carbon sequestration, marine and freshwater aquaculture, and atmospheric deposition of nitrogen and sulfur compounds. These programs directly or indirectly address ocean acidification and improve resilience to ocean acidification by helping to invigorate coastal economies, strengthen national food security, and improve the health of the atmosphere, water resources, and ocean.

United States Department of State

The Department of State, through the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (OES), engages with the world to build a healthier planet, a goal essential to the vitality and security of our Nation – and other nations – today and into the future. The Department of State, through OES, champions the role of science, technology, and innovation in foreign policy as an integral element of strengthening relationships, informing policy decisions, solving problems, and stimulating economic growth. OES issues, including ocean acidification and other climate-related impacts on the ocean, are part of the fabric of United States bilateral, regional, and multilateral relationships and typically represent positive aspects for engagement within the broad foundation that defines these relationships. Engaging on ocean acidification and other scientific issues provides the United States with opportunities to advance stability and economic growth globally.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The official mission of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) within the Department of the Interior is to work with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. The FWS is responsible for managing or co- managing 4 marine national monuments and 180 coastal wildlife refuges, including 118 designated marine protected areas. Ocean acidification will likely impact all of these monuments, refuges, and protected areas to some degree. It is important that the FWS understand the effects of ocean acidification on trust species (migratory birds, species listed under the Endangered Species Act, inter- jurisdiction fishes, marine mammals) as well as entire ecosystems.

United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey have projects that address ocean acidification issues and are relevant to the USGS mission. These projects are threaded through multiple USGS programs, including Coastal and Marine Geology and Ecosystems Programs. Guidance for USGS ocean acidification research is defined in two of the seven USGS mission area science strategies: Climate and Land Use Change and Ecosystems. One major goal under the Ecosystems mission area is to advance the understanding of how various anthropogenic and natural drivers influence ecosystem change. In that capacity, USGS work, in collaboration with other Federal government and academic efforts, focuses on investigating the magnitude of ocean acidification in various ecosystems and the ecosystem impacts of ocean acidification, including the degradation of marine systems and effects on of ocean acidification on carbonate producing organisms.

Four science projects with tasks that the USGS has implemented since 2009 to advance the Federal response to ocean acidification include: Florida Shelf Ecosystems Response to Climate Change, Arctic Ocean Acidification, Coral Reef Ecosystem Study, and Exploring the Links between Coral Reefs and Mangroves. Two technical projects that have been implemented are CO2calc, a software program that facilitates the study of ocean acidification by making carbon chemistry calculations easier to do, and the development of a pH photometer (light-sensitive machinery) for use in a variety of aquatic environments.

The Strategic Plan for Federal Research and Monitoring of Ocean Acidification will guide federal research and monitoring investments that will improve our understanding of ocean acidification, its potential impacts on marine species and ecosystems, and adaptation and mitigation strategies. This is the second Strategic Plan and is an update to the first version released in 2014. The Strategic Plan contains objectives and action items organized around seven thematic areas:

- Research

- Monitoring

- Modeling

- Technology development

- Socioeconomic impacts

- Education, outreach, and engagement strategies

- Data management and integration

Some highlights of the plan’s action items include:

- Expand coastal acidification monitoring in the nearshore and estuaries

- Expand certified reference material production for seawater pH measurements

- Identify and support human communities vulnerable to acidification through co-production of knowledge

- Develop synthesis products at coastal and regional scales to guide model development

The plan was developed by the Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification as part of the Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Act of 2009 (FOARAM Act; 33 U.S.C. Chapter 50, Sec. 3701-3708).

Eighth Report on Federally Funded Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Activities

This report describes federally funded ocean acidification activities during fiscal years 2022 and 2023. The report describes projects that were funded across the federal government, organized by region and then by thematic area. Budget tables are included that detail the amount spent by each agency on each thematic area. From

Farming of Seagrasses and Seaweeds: Responsible Restoration & Revenue Generation

The Interagency Working Group for Farming Seaweeds and Seagrasses produced this report that explores opportunities for farming seaweeds and seagrasses to deacidify ocean environments and provide agricultural products, such as livestock feeds.

Ocean Acidification Monitoring Prioritization Plan

The Ocean Acidification Monitoring Prioritization Plan details how to guide U.S. government efforts towards monitoring that could be deployed to meet the gaps described in the Ocean Chemistry Coastal Community Vulnerability Assessment. The plan is complementary to the Strategic Plan for Federal Monitoring and Research of Ocean Acidification, the U.S.

Second Strategic Plan for Federal Research and Monitoring of Ocean Acidification

The Strategic Plan for Federal Research and Monitoring of Ocean Acidification will guide federal research and monitoring investments that will improve our understanding of ocean acidification, its potential impacts on marine species and ecosystems, and adaptation and mitigation strategies. This is the second Strategic Plan and is an update to

Seventh Report on Federally Funded Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Activities

This report describes federally funded ocean acidification activities during fiscal years 2020 and 2021. The report describes projects that were funded across the federal government, organized by region and then by thematic area. Budget tables are included that detail the amount spent by each agency on each thematic area. From

The Ocean Acidification Information Exchange is a new online community catalyzing response to ocean and coastal acidification through collaboration and information sharing. If you are working on or interested in ocean and/or coastal acidification, come join the conversation! Members of the OA Information Exchange are using the site’s platform to swap ideas, exchange resources, and interact with people in a variety of disciplines across many regions. Together, we are building a well-informed community working to respond and adapt to ocean and coastal acidification.

We welcome members of government, tribal and academic research scientists, citizen scientists, experiential and formal educators, NGO employees, marine resources managers, policy makers, concerned citizens, aquaculturists, people in the fishing industry, technology developers, data managers, and others.

Learn more about the OA Information Exchange at www.OAInfoExchange.org or request an account!

Contact Us

Dwight Gledhill

Chair IWG-OA

NOAA Ocean Acidification Program Acting Director

dwight.gledhill@noaa.gov